Learning is a fundamental aspect of human life. But how we learn best is an ongoing debate. Our new paper in Scientific Reports suggests that we can use our ability to navigate to acquire abstract knowledge.

In embodied learning studies, researchers gather evidence for the idea that physical interaction aids learning. Material can be visualized, children may use their fingers to count, or a molecule can be built with bricks. However, not all types of knowledge are structured in a way that makes it easy to give some sort of physical form.

In our study that is now published in Scientific Reports, we used what we know about spatial navigation to find a way to apply a physical structure to abstract knowledge: the cognitive map. This is a map-like internal representation of the space around us that lets us plan routes, link information and infer relationships, for example to find shortcuts.

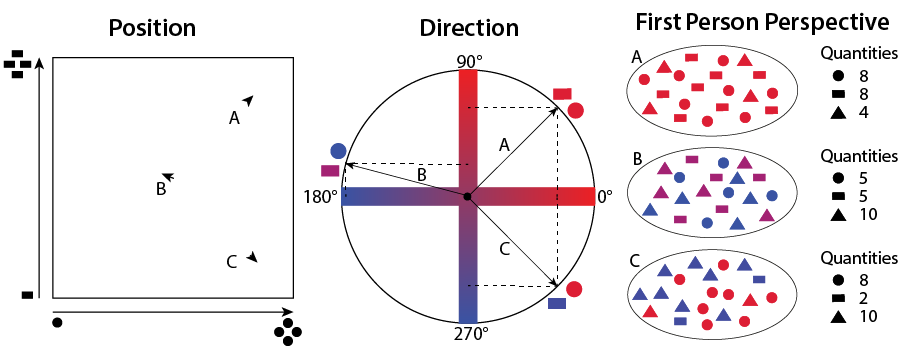

We set out to design a task in which abstract knowledge was organized in a map-like fashion, so that it could be navigated using physical movements. To this end, we used a two-dimensional quantity space, defined by the amount of circles and amount of rectangles presented to the participant. We further included directional information by adding a colour code to the shapes. Thus, participants were able to move through the space by walking and turning.

Here we depict the quantity space. Position is encoded in the number of circles and rectangles presented to the participant, direction is encoded in the color of the shapes as shown in the three examples A,B and C.

Participants completed several different tasks in our study which were all aimed to test their understanding of the abstract space.

We found that participants learned to find their way to goals in the space, could point into the direction of certain positions and estimate the distance to these positions. They further showed great improvements in their understanding of the space. We did not find an effect of physical movement, which may be due to some limiting factors such as hardware inaccuracies, exhaustion and immediate testing.

Overall our paradigm shows that a map-like structure poses an exciting opportunity to give even abstract knowledge an interactive frame, making use of well-trained spatial navigation behaviour as an embodied learning strategy.